SwiftUI: Persistent Pickers - How To

The humble picker is an important part of many user interfaces, and has many uses. This article addresses two things: how do we use it in SwiftUI? And how do we make sure that the choices users select using the picker are actually saved when the user closes the app?

First, we need to consider style.

It is possible to define a custom style for a picker: however in most cases the styles provided by SwiftUI work just fine. These all conform to the protocol PickerStyle, and are applied like this:

Picker("This is a picker", selection: whatever) {

// picker code

}

.pickerStyle(examplePickerStyle())

Provided Styles

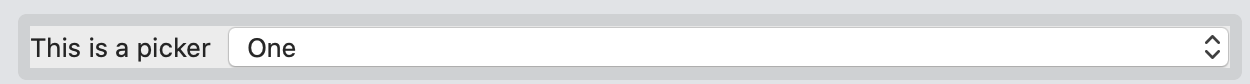

- DefaultPickerStyle: on iOS and watchOS this defaults to a wheel, whereas on macOS it defaults to a pop-up button. On tvOS the default is a segmented control. This makes it excellent for cross-platform apps, as none of the individual styles work on every platform.

- PopUpButtonPickerStyle: exclusive to macOS 10.15+, this is to be used when there are more than five options. Here the button itself indicates the selected option. As the Apple documentation for this states, you can also include additional controls in the set of options, such as a button to customise the list presented.

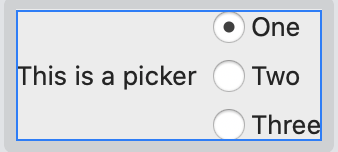

- RadioGroupPickerStyle: another macOS 10.15+ exclusive, this is to be used when there are two to five options. Apple recommend that for each option’s label, sentence-style capitalisation should be used. They also recommend not to use ending punctuation.

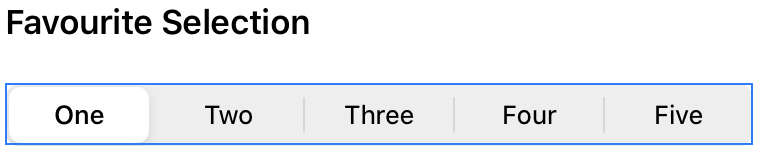

- SegmentedPickerStyle: available on iOS 13+, macOS 10.15+, tvOS 13+, and also with Mac Catalyst 13.0 (but not watchOS). This style supports Text and Image segments only. It’s good for cross-platform apps that don’t need to run on watchOS.

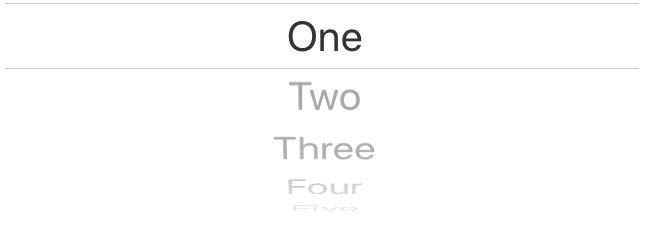

- WheelPickerStyle: available on watchOS 6.0+, Mac Catalyst 13.0+ and iOS 13+, this picker style has good platform coverage (with only tvOS excluded) and is pretty common as a result (a good example can be found in the EA Sports Fifa 20 Companion App). It’s important to organise options for this picker in a predictable order, as most won’t be visible immediately to the user. Apple suggest alphabetical order: it’s up to you what you choose for your app.

Implementing Functionality

Selection Binding

Once you’ve chosen a style, it’s time to implement your picker’s functionality. Pickers need three main things: a selection binding, a label, and content to display. Let’s look at the selection binding first. In SwiftUI, this is passed as (selection: ) and is the second parameter, after the picker label.

- Set the selection parameter to a bound property that provides the value to display as the current selection (for example an enum like so:)

enum Club: String, CaseIterable {

case arsenal = "Arsenal"

case doncaster = "Doncaster"

case burton = "Burton"

case oxford = "Oxford"

case portsmouth = "Portsmouth"

}

Bound Property/ Binding

A bound property in SwiftUI is called a binding. It is an example of a property wrapper type that can be used to create a connection, going both ways, between a property that stores data (i.e. a variable) and a view that displays and/or changes the data. Apple describe this as connecting a property to a source of truth stored elsewhere, rather than storing data directly. It also allows us to share the value in both places, making life easier when coding.

Property Wrapper

A structure that encapsulates read and write access to the property and adds any additional behaviour. This means that it controls which methods, etc. can read and write to the property and what further behaviour the property needs to exhibit.

Implementing Functionality II: Labels, Content

- Set the label to whatever you want.

- Then provide the content, usually in the form of either Text or Image. Append a .tag to each entry so that the type of each selection matches the type of the corresponding bound state variable, otherwise your picker won’t work.

// Should now look like this:

struct Whatever: View

{

enum Selection: String, CaseIterable, Identifiable {

case One

case Two

case Three

var id: String { self.rawValue }

// this will eventually allow for iteration

}

@ State private var selectedSelection = Selection.One

var body: some View {

Picker("This is a picker", selection: $selectedSelection) {

Text("One").tag(Selection.One)

Text("Two").tag(Selection.Two)

Text("Three").tag(Selection.Three)

}

.pickerStyle(DefaultPickerStyle())

}

Using ForEach

Fortunately, you don’t need to explicitly list each option, as seen in the example above. In my Stadiums application, I had 92 clubs to choose from, and some pickers will need to choose from even more options. Instead, just use ForEach, like so:

// Much, much easier.

enum Selection: String, CaseIterable, Identifiable {

case One

case Two

case Three

case Four

case Five

var id: String { self.rawValue }

// this will eventually allow for iteration

}

@ State private var selectedSelection = Selection.One

Picker("This is a picker", selection: $selectedSelection) {

ForEach(Selection.allCases) { selection in

Text(selection.rawValue)

// can also capitalise as requested by just adding .capitalized here

}

}

.pickerStyle(defaultPickerStyle())

The above is only possible if your Selection conforms to the Identifiable protocol: if it doesn’t, you need an explicit tag, like this:

enum Selection: String, CaseIterable {

case One

case Two

case Three

case Four

case Five

var id: String { self.rawValue }

// this will eventually allow for iteration

}

extension SelectionExtension {

var selectedSelection: Selection {

switch self {

case .One: return .Two

case .Two return .Three

}

}

}

@ State private var selectedSelection = Selection.One

Picker("This is a picker", selection: $selectedSelection) {

ForEach(Selection.allCases) { selection in

Text(selection.rawValue)

.tag(selection.selectedSelection)

// can also capitalise as requested by just adding .capitalized here

}

}

.pickerStyle(defaultPickerStyle())

Persistent Pickers

Now you should have a picker that looks good and functions well when you test it. Close the app, however, and you might notice that your choice hasn’t been saved when you re-open the app.

In a lot of situations, this is fine, and the picker choice doesn’t need to be saved. When I was developing my most recent app, Stadiums, however, I had a picker that let the user choose their favourite club. This was something that definitely did need to be saved, so that their favourite club didn’t reset every time they opened the app.

First, I needed to consider my options with regards to actually storing data persistently (i.e. after the user closes the app). The data in question was not of great size, being in essence a String, and so my thoughts immediately turned to UserDefaults. This can be used to store data (as long as it’s of any basic type: Bool, Float, Double, Int, String, URL - but also arrays, dictionaries, Date and Data) for as long as the app is installed. When you write data to UserDefaults, it automatically gets loaded on app start-up so it can be read back again. As you might have guessed, too much in UserDefaults will make your app slow to load (100KB is the generally accepted limit).

Implementing this functionality is a little more complex than just UserDefaults, however. After hours on Google, I realised I would also need to use an ObservedObject. Classes that conform to ObservableObject can be used in more than one view (useful), and @ObservedObject allows for sharing across multiple views and custom types, while also being very similar to @State. Any type with ObservedObject, however, is always going to conform to ObservableObject protocol, and this was the case in my project.

This next part is a lot more complicated, and requires a bit more code. I’ll break it down into steps.

Step One: Creating the ObservedObject and the State.

// more and more complicated, but it'll be worth it!

struct whatever: View {

@ObservedObject var settingsStore: SettingsStore = SettingsStore()

@State var selectedSelection: [Selection] = // all cases go here

var body some View {

}

}

Step Two: Creating the SettingsStore class conforming to ObservableObject.

Check your imports, and make sure you’ve imported SwiftUI AND Combine.

final class SettingsStore: ObservableObject {

// these 2 need to be different: Selection is the one you'll use in the picker

let theSelection = PassthroughSubject<Void, Never>()

var selectedSelection: Selection = UserDefaults.selectedSelection {

// set method

willSet {

UserDefaults.selectedSelection = newValue

print(UserDefaults.selectedSelection)

theSelection.send()

}

}

}

As you can see, this class is a bit more complicated. First, we create a PassthroughSubject, which is why we need Combine. It doesn’t have an initial value, and lets us adapt our existing imperative code to Combine (which, like SwiftUI, is declarative). Theory aside, its practical use here is to allow us to send new values through to our objects(i.e. when our picker is updated). The rest of the code implements UserDefaults, making sure our choice is stored there, and then also calls send on our other, PassthroughSubject variable (with its suspiciously similar name). This slightly tangled mess of code ensures two things: one, that our value is saved in UserDefaults, and two, that the separate but similar value storing the current choice is updated using PassthroughSubject. This ensures that our data continues to flow, and that it is correct.

Step Three: UserDefaults

Our code before is great, but it doesn’t actually work. For it to work, we need to implement UserDefaults properly, and for that we need to use an extension. If you’ve not used one before, here’s the definition:

Extension (Swift)

Extensions add new functionality to an existing class, structure, enum, or protocol type. They can even do this if we don’t have access to the original source code of that class (retroactive functionality). Examples of their use include adding functions and computed properties, providing new initialisers (i.e. constructors), defining and using new nested types, making existing types conform to a protocol, and adding default implementations to protocols with protocol extensions.

Our extension is intended to add functionality to UserDefaults. In this case, we’re going to add a private struct, to provide the Keys UserDefaults wants, and we’re also going to add custom get and set methods for our properties. First, we should define the struct.

extension UserDefaults {

private struct Keys {

static let selectedSelection = "selectedSelection"

}

}

UserDefaults searches for objects by their Key, using forKey. As such, we want our selectedSelections to all have the same Key, which we’ve just defined. Now, we need to define our get and set methods.

extension UserDefaults {

private struct Keys {

static let selectedSelection = "selectedSelection"

}

static var selectedSelection: Selection {

get {

if let value = UserDefaults.standard.object(forKey: Keys.selectedSelection) as? String {

return Selection(rawValue: value)!

}

else {

return .One

}

}

set {

UserDefaults.standard.set(newValue.rawValue, forKey: Keys.selectedSelection)

}

}

}

}

Step Four: Finish

That’s a lot of code, so let’s break it down. We’ve already covered Keys, so let’s proceed to our static var, selectedSelection. We already defined the enum for this earlier, so we make sure it conforms to that (Selection). Then, we define the methods. To get the selectedSelection, we use if let: this will check in UserDefaults for our value (which will be stored as String, and also might not be stored yet: hence the need to use optionality with the ?, as this could return nil). If it’s there, it will be returned, using rawValue and the ! to unwrap it (because if UserDefaults does contain our choice, we know that the optional variable we’re using does definitely have a value - hence it’s safe for us to unwrap. Probably.). We also have else: if nothing can be found in UserDefaults (for example if we haven’t made a choice yet), the first picker option will be returned.

Next, we have our set method. This goes right back to where we started - the idea of using UserDefaults to persistently store a value. Now we’ve done all that work, this just takes a single line, passing it our selectedSelection key as the forKey parameter, and newValue.rawValue to save our choice.

And now we’re done, so congratulations! You now have a picker that will save your choice so that it is not deleted when the user closes your app. Full code below and on my GitHub

Full Code

import SwiftUI

import Combine

enum Selection: String, CaseIterable {

case One = "One"

case Two = "Two"

case Three = "Three"

case Four = "Four"

case Five = "Five"

}

struct PersistentPicker: View {

@ObservedObject var settingsStore: SettingsStore = SettingsStore()

@State var clubIndex = 1

@State var selectedSelection: [Selection] = [.One, .Two, .Three, .Four, .Five]

var body: some View {

List {

Text("Fav Selection: \(self.settingsStore.selectedSelection.rawValue)")

// now: somehow pass this to the other view

VStack(alignment: .leading, spacing: 20) {

Text("Favourite Selection").bold()

Picker("", selection: self.$settingsStore.selectedSelection) {

ForEach(self.selectedSelection, id: \.self) { Fav in

Text(Fav.rawValue).tag(Fav)

}

}

.pickerStyle(WheelPickerStyle())

}

.padding(.top)

.padding(.top)

}

}

}

final class SettingsStore: ObservableObject {

let theSelection = PassthroughSubject<Void, Never>()

var selectedSelection: Selection = UserDefaults.selectedSelection {

willSet {

UserDefaults.selectedSelection = newValue

print(UserDefaults.selectedSelection)

theSelection.send()

}

}

}

extension UserDefaults {

private struct Keys {

static let selectedSelection = "selectedSelection"

}

static var selectedSelection: Selection {

get {

if let value = UserDefaults.standard.object(forKey: Keys.selectedSelection) as? String {

return Selection(rawValue: value)!

}

else {

return .One

}

}

set {

UserDefaults.standard.set(newValue.rawValue, forKey: Keys.selectedSelection)

}

}

}

struct PersistentPicker_Previews: PreviewProvider {

static var previews: some View {

PersistentPicker()

}

}